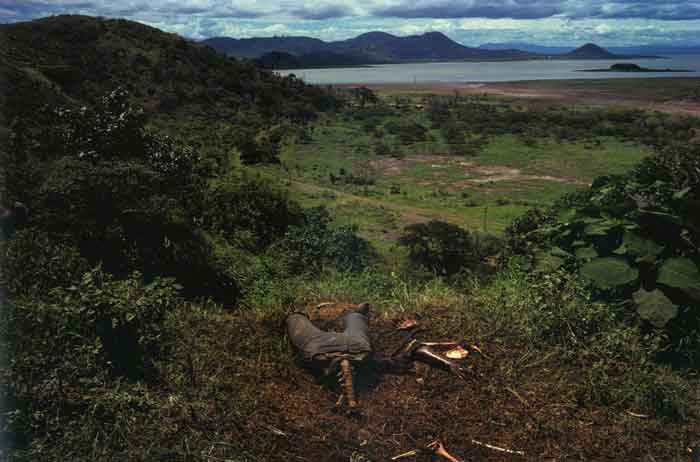

Susan Meiselas's iconic photograph "Cuesta del Plomo", hillside outside Managua, a well known site of many assassinations carried out by the National Guard. People searched here daily for missing persons.

Susan Meiselas's iconic photograph "Cuesta del Plomo", hillside outside Managua, a well known site of many assassinations carried out by the National Guard. People searched here daily for missing persons.

Nicaragua under the Somozas had been a reliable U.S. ally, but slipped through its grasp as the greediness and ghoulishness of Anastasio ("Tachito") Somoza Debayle turned pathological and became a gross liability to the United States.

A typical drill of Somoza's infamous National Guard:

"Who is the Guardia?"

"The Guardia is a tiger."

"What does tiger like?"

"Tiger likes blood."

"Whose blood?"

"The blood of the people."

The counterinsurgency experts in Washington learned from the Cuban

experience as well, but were unable to convince President Jimmy Carter

that human rights should not become a factor in determining US policy

toward its traditional spheres of control. Carter, because it was a matter

of faith, made human rights a leitmotif of his foreign policy.

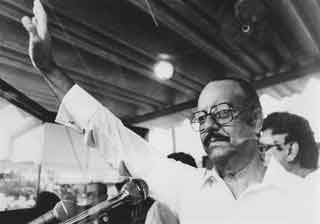

Anastasio ("Tachito") Somoza

Somoza was confused by Carter's apparent sincerity on the human

rights issue. His family had been installed in power by President Franklin

Roosevelt, the man who also had made human rights the center piece

of US policy in his Four Freedoms address during World War II. But

Roosevelt had never bothered the Somoza clan with complaints about

human rights violations. After all, forty-five years of anti-communist

obedience should have counted for more than a few cases of maltreating

radical trouble makers.

When Somoza finally realized that Carter was serious, he found

himself in an impossible position. To lift martial law for the purpose of

continuing to receive US aid and legitimation would also mean allowing

the FSLN to have the necessary space to organize throughout the

country. To abide by Carter's principles would require Somoza to leash

and muzzle the National Guard; to remove from it the very instruments

by which it had succeeded in terrorizing the population.

Somoza paid lip service to human rights, hoping that it would appease

the US ambassador, while at the same time he ordered the Guard to

wipe out Sandinista influence in me poor barrios and the Christian

based communities where the priests and nuns were applying their

revolutionary theology. However, the ambassador did not turn the other

way in 1977 and 1978 as Guard members murdered, tortured, raped

and looted their way through the barrios and rural areas. US officials

denounced the abuses, threatened to cut off aid, and eventually did so

in 1978. Subsequently writing from exile in Paraguay in the 1980s,

Somoza charged: 'Our nation was truly delivered into the hands of the

Marxist enemy by President Jimmy Carter and his administration. I was

betrayed by a longstanding and trusted ally.' Somoza had a point. Having

labeled the FSLN communists, and received encouragement and support

from right-wing friends in the US military and in Congress for forty

years, Somoza could not believe that the United States would allow the

'communists' to triumph.

But Carter believed he had a mandate to restore US credibility after

the stains left by the Vietnam War and the revelations of CIA

shenanigans - including its support for corrupt and brutal dictators.

The era of world politics had passed when American presidents could

with impunity maintain the Somozas of the Third World as reliable

clients.

Since Somoza had no desire to transform himself and his Praetorian

Guard into anything that could conceivably qualify as democracy, he

chose more repression. He thought that by increasing the level of

brutality the Guard could cow the populace back into obedience. He

was wrong. The more brutal the Guard's behavior, the more resistant

the populace grew. As Guard units marched through the barrios, or

randomly shot poor teenagers and middle-class youth, fear turned to

outrage. People who for decades had accepted the savageries of the

Guard could tolerate no more.

Inside Nicaragua and in the United States, the anti-Somoza forces

coalesced. Illiterate peasants and local merchants in Nicaragua found

themselves allied in the struggle against Somoza with exiled dish

washers in Houston and University of California students. Some became

guerrillas, while others served as lobbyists, pamphleteers, or fund raisers

in Washington. A group of well known professionals and business

executives formed 'Los Doce', a group of twelve reasonable and

responsible moderates who appealed to middle-class opinion throughout

the world to join in with money and moral support to oust the dictator

and his hated Guard.

In January 1978, an event occurred that galvanized the fragmented

anti-Somoza opposition. Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, the dynamic editor

of La Prensa, Managua's leading daily, was assassinated. The popular

Chamorro had openly published demands for Somoza's removal, and

called for broad national unity. Although lacking direct proof, most

Nicaraguans assumed Tachito had ordered the slaying. Chamorro, hardly

a leftist, had criticized the FSLN 's radical rhetoric, but the Sandinistas,

nevertheless, joined other anti-Somoza elements, including labor unions,

in organizing mass protests, strikes and demonstrations in response to

Chamorro's murder. By mid-1978 the Church had added its weight to

the growing demand that Somoza resign.

The US government was in the throes of a decisive policy debate.

President Carter faced a choice: Somoza, a flagrant rights violator; or

the FSLN, regarded in intelligence and diplomatic circles as communists,

or, at best, independent leftists friendly to Castro.

'Another Cuba' in Central America was deemed unacceptable, but

the continuation of Somoza rule appeared dubious. National Security

Adviser, Zbigniew Brzinski, feared that by applying human rights criteria

to Nicaragua, the United States would strengthen the revolutionaries.

Since the Guard was loyal to Somoza, not the Nicaraguan Constitution,

Tachito's removal would lead to its disintegration, Brzinksi believed.

The only armed force then remaining would be the FSLN. The human

rights activists inside the administration downplayed the Sandinista

threat and emphasized to the president the importance of maintaining

consistency on human rights. Carter compromised between the competing ideological wings of his administration.

Reversing nearly a century of tradition, President Carter asked Somoza

to step down as a way of ending the civil war, while retaining intact the

National Guard, whose loyalties should logically rum from Somoza to

its next benefactor, the United States. It was not an act of idealism, but

rather a realistic judgment on the part of the president. US intelligence

reports agreed that the tide had turned in Nicaragua and that the

dictator's days were numbered. But Carter's decision came too late for

the national security apparatus to save the Guard. The action on the

battlefields had ensured the Sandinistas their rightful place as heads of

State.

The battlefield included the very center of government in Managua.

On 23 August 1978, eleven months before Somoza fled and the Guard

collapsed, Sandinista soldiers dressed in Guard uniforms arrived in army

trucks at both entrances of the National Palace, where Somoza's

legislature convened. Using their best imitation of Guard officer speech,

they deceived the troops stationed at the doors and other posts. Once

inside, the Sandinistas held captive Somoza's friends, allies and even

family members. For Tachito it was supremely humiliating.

A demoralized Somoza yielded to the Sandinistas' demands for the

release of the Nicaraguan glitterati: $500,000 in exchange for safe

conduct from the palace to the airport, where the captors would be

flown to Cuba, plus the release of fifty-nine political prisoners. Even

National Guard officers winced when Somoza caved in. Morale sank

for a short time.

To revive the fighting spirit of his men, Somoza ordered unprecedentedly

vicious levels of reprisals against the revolutionaries. Inspired

by their palace victory, the Sandinistas called for uprisings. In Matagalpa.

according to the Nicaraguan press, 'armed youths in rebellion' took

over thirty city blocks. The Guard responded with artillery, armored

vehicles and heavy machine-gun fire to retake the neighborhood. On

August 27, the Catholic Church called upon Somoza to resign as 'the

only way to end the current political violence'.

In the final days of August the depressed Tachito regained the

ruthlessness that had made him the scourge of the nation. He purged

Guard officers who had criticized his weakness in bargaining with the

rebels. Charged and found guilty of conspiring to overthrow the

government were eighty-five Guardsmen, including twelve officers. As

for the 'communists and subversives', his name for all revolutionaries,

Somoza told his generals to show no mercy. Sandinisus or suspected

sympathizers were rounded up, tortured, interrogated and then killed.

The Guard carried out fishing expeditions in the barrios, targeting

especially the youth. Thousands of men and women were arrested and

shot simply because they were young. Instead of submitting, the public

were spurred to uncontainable rage.

Matagalpa. Nicaragua, 1978. Muchachos await the counterattack by the National Guard. (Susan Meiselas)

While the human rights advocates and the national security hawks debated policy in Washington, the Guard's ferocity claimed the attention of the world's media. And the Sandinistas, feeling the public pulse, struck. On 7 September 1978 guerrilla units descended from the mountains to launch a major offensive, attacking and holding parts of five major cities. Several thousand Sandinistas took part in the offensive, sending the Guard reeling. Los muchachos (teenagers and children) spearheaded the barrio insurrections.

Susan Meiselas's "untitled" 1979

Susan Meiselas's "untitled" 1979

In Leon, Grenada, Diriamba, Chinandega, Matagalpa and Managua,

the muchachos joined the uniformed guerrillas. They fought with weapons

stolen from the Guard, sticks, stones and home-crafted Molotov cocktails. Faced with the wrath of the people, the Guard did not flee, but counterattacked with artillery and aeria1 bombing. When the smoke

finally cleared and the Guard regained control, the bodies of young

boys and girls were strewn across the makeshift barricades and trenches.

Commercial and residential areas, schools and churches, looked like

Coventry after days of Axis bombing during World War II. Those

edifices that remained structurally in tact bore the scars of bullets and

shells.

The neighborhood of Monimbo, in the city of Masaya, rose up and

with home-made weapons and rocks held off the heavily armed troops,

then suffered the retaliation. 'We fought against the Guard to save our

lives,' recalled Ernesto Rodriguez Zelaya, a Monimbo mechanic. 'We

realized that after the [Guard's} "mopping up" operation life wasn't

worth anything. Whoever stayed home would be killed! It was easier

for us to grab a rifle and fight with the muchachos than stay home where

we would be just a target for the Guard. So it was the repression that

made us fight, because we didn't want to die.'

In February 1978, Monimbo residents rose again, fought with unbelievable

courage, using paving stones from Somoza's own factory as

weapons, and then faced the renewed vengeance of the Guard.

But even after the continued bombing and shelling of the area, the

Monimbo dwellers refused to submit. The Guard could not regain

control.

The behavior of the Monimbo populace dramatized a larger reality,

one that even jaded members of US intelligence could not escape: the

vast majority of Nicaraguans were prepared to endure immense pain

and suffering to rid themselves of the Somoza family and their Guard.

Tachito understood the people's loathing and responded accordingly.

He ordered his air force to bomb and strafe guerrilla-held cities. Even

after the FSLN had retreated, the air force continued to bomb, to

ensure that the populace would get the message. When the bodies were

counted, the Red Cross announced that over five thousand had perished

from Esteli, Masaya and Leon alone. A further 10,000 were missing;

15,000 were wounded; 30,000 were homeless. Refugees poured into

improvised camps just across the frontiers.

By May 1979 Somoza and his generals decided that the situation

looked bleak, and that if they were to reassume control of Nicaragua,

Masaya was the strategic place to begin. On June 9 the National Guard

began intensive bombing and strafing of Monimbo, 'the pissed off

barrio', as it became known. Following the bombing, a column of

Sherman tanks led Guard foot soldiers through the Sandinista controlled

neighborhoods to retake portions of Masaya.

The guerrillas beat a strategic retreat, but returned unexpectedly three

days later and retook most of the city. For two weeks the battle raged,

block by block. 'The Guard didn't push us out: a Sandinista officer

reported, 'because they didn't receive reinforcements, nor did we take

them out since we didn't have any ammunition.'

On June 24 Guard officers and men abandoned their Masaya

command post, using hundreds of political prisoners as a shield to cover

their retreat. The Sandinistas were in undisputed control of the city,

twenty miles south of Managua. Somoza spent his days in the bunker,

built on top of a Managua hill overlooking the Intercontinental Hotel.

One June evening he met members of the media in an 'off the record'

session. One reporter, nevertheless, recorded the conversation. Why

was he bombing his own people, destroying Nicaraguan property, he

was asked. 'What do you know about underdevelopment?' he slurred,

showing the effects of a day of drinking. 'My people are a bunch of

lazy, stupid, underdeveloped assholes.'

In late June, Tachito ordered his bombers to drop 500 pounders on

densely populated Managua neighborhoods. The Sandinistas, who had

taken the poor barrios from the Guard, immediately retreated to Masaya,

but the muchachos who survived the bombings continued to snipe at and

ambush the Guard in the capital. The US ambassador demanded that

Somoza resign, hoping that it was still not too late to save the Guard

except for its most notorious officers. Apart from unwavering support

from the Israeli government - of which Somoza had been a loyal supporter - and a few cohorts among the remaining Latin American

dictators, Tachito was isolated.

He knew the war was over, but nevertheless ordered his air force to

continue bombing. His family had stolen hundreds of millions of dollars

from the Nicaraguan people, and Tachito expressed his attitude toward

his victims as if to make a final statement that would etch into

Nicaraguan memory the essence of the cruelty that had characterized

the forty-five years of Somoza clan rule.

On July 17 the Somoza family fled to Miami, Florida. Without

Somoza's presence, there was nothing to hold the Guard together.

Overwhelmed and demoralized, the once invincible National Guard

collapsed. Some units surrendered to FSLN commanders, others fled

as one or in ragtag fashion to borders north and south. On July 19 the

Sandinistas held state power.

The Nicaragua Revolution triumphed, like the Cuban one twenty

years earlier, not just because of the Sandinistas' astute military strategy

and tactics employed, or the mistakes of the National Guard. A peculiar

conjuncture of events and times also created a setting on which the

decisive battles were fought. In Washington, the human rights element

in the administration temporarily obstructed national security interventionists;

Costa Rica provided unusual levels of help for the Sandinistas,

thanks to Somoza's 'bad neighbor' policy toward the San Jose

regime; in Cuba, a Solomon-like Fidel Castro persuaded the rival factions

of the FSLN to bury their ideological differences and unify.

The revolution could not have triumphed without the ambivalence

of President Carter, just as its subsequent programs could not be realized

without a similar kind of vacillation from the Reagan administration.

The Sandinistas captured world opinion, an intangible factor that

nevertheless wove its way through White House thinking and mass

media concepts and images. Somoza had made fundamental errors in

judgment. His tactics had alienated even the wealthy, who had for

decades accepted the caprices of his family rule.

The Somozas had accumulated more than 5500 million during their

dynastic rule. They possessed one fifth of Nicaragua's arable land and

more than one hundred and fifty businesses. In addition, the family had

accounts and assets in the United States and Europe that were believed

to be more than double what they owned in Nicaragua. Somoza believed

that as long as the United States was interested in maintaining its

hegemony, the US government would protect him. Tachito's contempt

for his own countrymen and women was so great that it did not occur to him that Nicaraguans could play a role in determining the fate of

their nation.

THE GUERRILLA WARS OF CENTRAL AMERICA, Saul Landau