Jacobo Arbenz

The CIA was established in 1947—the same year Washington served

notice that its support for Latin American democracy was conditional

on the maintenance of order-and began to develop contacts among

military officers, religious leaders, and politicians it identified as bulwarks

of stability. Yet it was not until 1954 that it would execute its

first full-scale covert operation in Latin America, overthrowing

Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz and installing a more pliant successor.

Arbenz, as CIA analysts and most historians today admit, was

trying to implement a New Deal-style economic program to modernize

and humanize Guatemala's brutal plantation economy. His only

crime was to expropriate, with full compensation, uncultivated United

Fruit Company land and legalize the Communist Party—both unacceptable

acts from Washington's early-1950s vantage point.

Operation PRSUCCESS, as the CIA called its Guatemalan campaign,

was the agency's most comprehensive covert action to date,

much more ambitious than its operations in postwar Italy and France

or in Iran the year before. Unlike the ouster of the Iranian prime

minister, Mohammad Mossadeq, which took a mere couple

of weeks, Arbenz's overthrow required nearly a year.

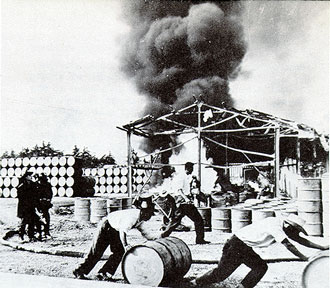

Gasoline depot bombed by CIA rebel air force

In addition to

destabilizing Guatemala's economy, isolating the country diplomatically

through the OAS, and training a mercenary force in Honduras,

the Guatemalan campaign gave CIA operatives the chance to tryout

new psych-war techniques gleaned from behavioral social sciences.

They worked with local agents to plant stories in the Guatemalan

and U.S. press, engineer death threats, and conduct a bombing

campaign—all designed to generate anxiety and uncertainty.

They organized

phantom groups, such as the "Organization of Militant Godless,"

and spread rumors that the government was going to ban Holy

Week, exile the archbishop, confiscate bank accounts, expropriate all

private property, and force children into reeducation centers. Operatives

studied pop sociologies and grifter novels and worked closely

with Edward Bernays, a pioneer in public propaganda (and Sigmund

Freud's nephew), to apply disinformation tactics. Borrowing from

Orson Welles's War of the Worlds, they transmitted radio shows—taped

in Florida and beamed in from Nicaragua—that made it seem as

if a widespread underground resistance movement were gaining

strength; they even managed to stage on-the-air battles.

In the 1950s, the Cold War was often presented as a battle of

ideas, yet CIA agents on the ground didn't see it that way. They

rejected the advice of their Guatemalan allies that the campaign

include an educational component, instead insisting on a strategy intended

to inspire fear more than virtue . Propaganda designed to "attack

the theoretical foundations of the enemy" was misplaced, one

field operative wrote; psychological efforts should be directed at the

"heart, the stomach and the liver (fear)." We are not running a

popularity contest but an uprising," rejoined one agent to Guatemalan

concerns that the campaign was too negative. U.S. planes flew low

over the capital, dropping propaganda material, which for a region

that hadn't seen aerial warfare since the marine campaign against

Sandino sent a message beyond what was printed on the flyers. "I

suppose it doesn't really matter what the leaflets say," said Tracy

Barnes, who led the operation.

The "most effective leallet drops during the operations," concluded

a CIA postmortem of the coup, "were those followed by a successful

military blow." Such blows were delivered by CIA assets in

country, who bombed roads, bridges, military installations, and property

owned by government supporters. The agency distributed sabotage

manuals that provided illustrated, step-by-step instructions on

how to make pipe bombs, time bombs, remote fuses, chemical, nitroglycerine,

and dynamite bombs, even explosives hidden in pens, books,

and rocks. A how-to guide exhorted Guatemalans to take up violence

in the name of liberty, noting that "sabotage, like all things in life, is

good or bad depending on whether its objective is good or bad."

Such a "terror program" worked. Arbenz fell not because psych

ops had won the hearts and minds of the population but because the

military refused to defend him, fearing Washington's wrath if it repelled

the mercenaries.

At least some American leaders were fully aware that the

Guatemalan intervention marked a watershed in inter-American relations,

and they did their best to limit its damage. Assistant Secretary

of State Mann, for example, admitted in a private memo that

CIA efforts to oust Arbenz represented Washington's first full-scale

"violation of the Non-intervention Agreement," the "first of its kind

since the establishment of the Good Neighbor Policy." Yet he hoped

to hold on to the idea of the Good Neighbor policy, even as the

United States corrupted its language and institutions. He therefore

gave instructions that each step in the coup "should be justified on

technical grounds" to allow the United States to claim plausibly that

it was acting within the letter, if not the spirit, of Roosevelt's nonintervention

pledge.

But on the heels of Guatemala came Cuba in 1959, a revolution

that the CIA found itself powerless to reverse—even though it modeled

its 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, which sought to topple Castro, on

its earlier successful Guatemalan operation. Cuban revolutionaries

learned well from the Guatemalan experience. Ernesto "Che" Guevara

in fact was in Guatemala in 1954, having concluded his famous

motorcycle tour of South America to work as a young, socially conscious

doctor. He witnessed firsthand the effects of U.S. intervention,

taking refuge in the Argentine embassy, where he would meet

a number of other future Latin American revolutionaries. After a

time cooling his heels, he won safe passage to Mexico, where he

joined Fidel Castro's revolutionary movement in exile. "Cuba will

not be Guatemala," he liked to taunt Washington.

Empire's Workshop, Greg Grandin