Costa Rica's Changing Economy

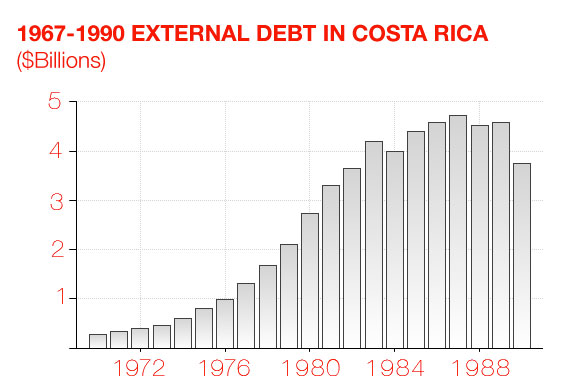

Costa Rica's external debt tripled from 1977 to 1981, and has since almost doubled to over $4 billion, with new loans of $500 million in 1988 and a trade deficit of $200 million a year. Current debt to private banks amounts to $200 million in interest alone, but though payment is largely suspended, the international lending institutions keep the funds flowing. "Costa Rica has lost the ability to determine its own economic future," the San Jose journal Mesoamerica concluded in mid-1988, reporting that real wages had fallen 42 percent in the preceding five years, as prices increased while subsidies for food and medicine were reduced or eliminated. The infant mortality rate had risen sharply in certain areas, primarily because of the economic crisis and increasing hunger, according to the University of Costa Rica's Institute for Health Research. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) demanded further cuts in social spending, lowering of the minimum wage, and cutting of government employees, "thus jeopardizing what had been one of the most enlightened social service programs in Latin America," Mesoamerica reports. Once self-sufficient in agriculture, Costa Rica is now importing staples as it shifts to largely foreign-controlled exports, including export crops, in line with traditional IMF-World Bank-USAID directives, a familiar recipe for disaster in Third World countries. "Arias's pro-big business economic strategy," COHA observes, may turn large numbers of once self-sufficient farmers to wage laborers on agribusiness plantations while profits are largely expatriated, "a major change of philosophy in a country that has had a strong state-directed welfare orientation."

Necessary Illusions, Chomsky