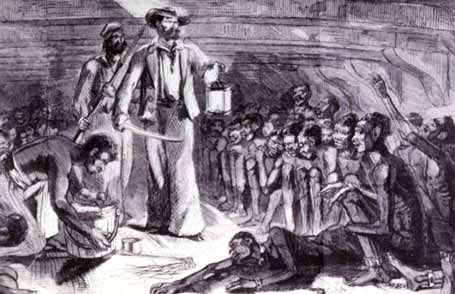

The slaves were called the "coins of the Indies" when they were measured, weighed and embarked in Luanda in the Portuguese colony of Angola; in Brazil those surviving the ocean voyage became "the hands and feet" of the white master. Angola exported Bantu slaves and elephant tusks in exchange for clothing, liquor, and firearms, but Ouro Preto miners preferred blacks shipped from the little beach of Ouidah on the Gulf of Guinea because they were more vigorous, lasted somewhat longer, and had the magic power to find gold. Every miner also needed a black mistress from Ouidah to bring him luck on his expeditions. (In Cuba, medicinal powers were attributed to female slaves. According to onetime slave Esteban Montejo, "There was one type of sickness the whites picked up, a sickness of the veins and male organs. It could only be got rid of with black women; if the man who had it slept with a Negress he was cured immediately.") Ouro Preto's appetite for slaves became insatiable; they expired in short order, only in rare cases enduring the seven years of continuous labor. Yet the Portuguese were meticulous in baptizing them all before they crossed the Atlantic, and once in Brazil they were obliged to attend mass, although they were not allowed to sit in the pews or to enter the chanel.

The gold explosion not only increased the importation of slaves, but absorbed a good part of the black labor from the sugar and tobacco plantations elsewhere in Brazil, leaving them without hands. The miners were contemptuous of farming, and in 1700 and 1713, in the full flush of prosperity, hunger stalked the region: millionaires had to eat cats, rats, ants, and birds of prey. A royal decree in 1711 banned the sale of slaves occupied in agriculture, with the exception of those who showed "perversity of character."