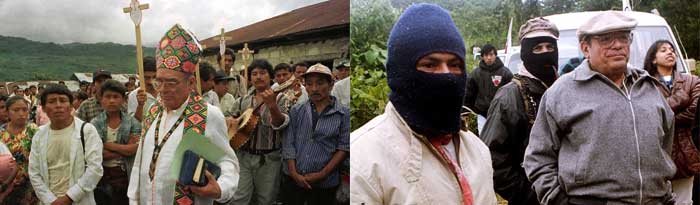

"An indigenous-centered Catholicism"

In 1960, Samual Ruiz Garcia is named Bishop of San Cristobal de las Casas. After the Medellin Council of Latin American Bishops in 1968, Ruiz begins to promote liberation theology and an indigenous-centered Catholicism.

Zapatista Timeline by Tom Hansen and Enlace Civil

Bishop Samuel Ruiz often said that, when he was appointed to the diocese in 1959, he found little or nothing had changed in the plight of the indigenous people since the time of Las Casas, nearly 500 years ago. His own life started in poverty: the eldest of 5 children, his parents struggled to survive on a shared smallholding and a little grocery shop in Irapuato, in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato. Schooled irregular at first, in part because of stringent laws against Catholics and their schools in the 1930s post-revolutionary era of persecution of the Mexican Church. At the age of 13, however, things changed when he joined the diocesan minor seminary, even though it was not strictly legal at the time and had no fixed abode. He subsequently had a brilliant early career in the Church, going from the seminary in Mexico to ordination, postgraduate studies and a doctorate in biblical studies in Rome after World War II. On his return to Mexico he became firstly a teacher, then rector of the diocesan seminary in León and subsequently a canon of León Cathedral, before being made Bishop of San Cristobal at the early age of 35.

When he arrived in Chiapas, the state seemed stuck in its past, but the Church in Latin America had begun a process of change, still moving today, although the new bishop was not initially aware of the shape this was taking. The Council of Latin American Bishops (CELAM) met for the first time in Rio de Janeiro in 1955 and the Catholic Church on the sub-continent started to bring together its experiences. Ruiz first followed his predecessor in encouraging the work of catechists, who by their service and the example of their own lives inspired the rest of the community. Later, he criticized this approach for its orientation towards Western attitudes and organization from the top down rather than from among the people themselves using their own cultural values. This comment comes from what is really his own testament to his work, the pastoral letter he wrote to his diocese on the occasion of the visit of Pope John Paul II to the south of Mexico in August 1993, En Esta Hora de Gracia (‘In This Hour of Grace’).

From this and other sources one can sketch what Don Samuel considered to be his own growth in understanding, his ‘conversion’ as he himself called it. He was at the Second Vatican Council and was impressed by the part played by the bishops from Africa in putting together the decree, Ad Gentes about the Church's missionary activity. They were lobbying strongly for a new approach to Christian anthropology, he said on a radio program in his retirement, which would help them more with their missionary work and value the dignity of different cultures. He referred often to the influence that Ad Gentes had on him at a time when he says he himself was still thinking of ways to teach his people to substitute Spanish for their own indigenous languages in order to evangelize them and help them economically. He began to see more clearly that the Spanish missionaries had not come just to evangelize but also to impose their culture. And now here was Ad Gentes, advising Christians to familiarize themselves with their own national and religious traditions and seek out the seeds of The Word that lay latent within these.

The ‘conversion’ did not stop there. In 1968, CELAM's second conference in Medellín, Colombia, looked at ways of making Vatican II more readily applicable to the Latin American context. There was a dramatic refocusing towards the widespread misery on the sub-continent, resulting from unjust social and economic structures which the poor were powerless to change. This attention to ‘institutionalised violence’, made a profound impression. So the catechists in Don Samuel’s diocese became the spokespeople of their communities, which were considering all aspects – social, political, economic and cultural – of their situation in order to work out where the Spirit of God was leading them.

The next point of departure on Don Samuel’s road was the 1974 Congress of the Indigenous he held in San Cristobal. The communities had elected speakers whom they felt led straight lives and could represent them. The catechists of the diocese now were not just there to help with traditional catechetics, with services and singing, but were genuine representatives of their communities in all the matters most important to them. There followed three days of lament for all the abuses that the indigenous peoples had suffered, with details, but also concrete suggestions about what to do in each case. By then, Don Samuel could speak two of the four languages of the indigenous present with a working knowledge of the others. He learned enough at the meeting to see the inadequacy of his diocesan pastoral plan, which he scrapped there and then and developed another based on what he had heard.

The 1979 third conference of CELAM in Puebla, Mexico reinforced Don Samuel’s thinking through its advice to the Church to pursue a path of preferential option for the poor, including the 75 per cent of the people of the diocese of San Cristobal who were indigenous as well as many of those who were not. He quoted the Book of Exodus as a start in trying to help his people follow this directive: ‘I have seen the miserable state of my people in Egypt. I have heard their appeal to be free of their slave drivers. Yes, I am well aware of their sufferings.’ He also had something to say to the rest of us, interpreting St Matthew: ‘Men are blessed when, moved by the Spirit of God, they show solidarity with the poor.’

It was the fourth conference of CELAM, at Santo Domingo in 1992 that in many ways satisfied Don Samuel most. In the final document’s reflections on the indigenous peoples, he explain why. ‘The action of God, through his Spirit, is present within all cultures’. ‘One task of evangelization, conducted in terms of the culture, will always be the salvation and comprehensive liberation of a particular people or human group’. Don Samuel’s growing belief and commitment of the previous 30 years now had the unequivocal backing of the Church. The Church had answered the question, at least in theory, once posed to him by one of his people: ‘If the Church does not make itself Tzeltal with the Tzeltal people, or Ch’ol with the Ch’ol people or Tojolobal with the Tojolobales, how can it call itself Catholic?’

Excerpted and edited from Gerald MacCarthy's Forming a Church with his Indigenous People: The work of Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia